Brunel’s design and construction of Nightingale’s hospital in the Crimea, by Anthony Lambert

posted on 12/06/20

The Nightingale hospitals built in various British cities to take coronavirus patients have been in the news of recent months. Even those with limited knowledge of the Crimean War know of the way Florence Nightingale improved medical conditions for the injured troops at the hospital in Scutari. Less well known is the role played by another hero of the Victorian age, the great engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

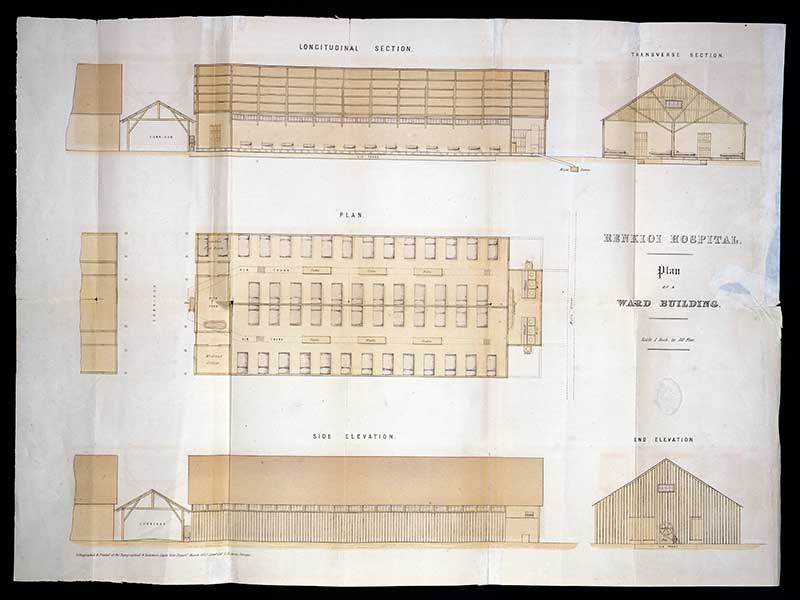

Florence Nightingale arrived at Scutari in November 1854 with 37 volunteer nurses. She made sure that the British press soon knew of the appalling conditions in the hospital. Among the worst of its defects was a water supply that flowed through the rotting carcass of a dead horse. The revelations caused such a scandal that the government fell. The incoming Lord Palmerston sent out a Sanitary Commission, and in February 1855 Brunel was asked to design a prefabricated hospital that could be quickly manufactured in England and sent out for assembly in the Crimea. Within six days he had designed a hospital for 1,000 patients in wards of 24, incorporating innovative ventilation, water closets, basins, baths, drainage and temperature control mechanisms.

Brunel shared with Nightingale a withering contempt for red-tape and officialdom, and he placed contracts for the work without reference to the War Office Contracts Department. The squeals of protest from the department at this unorthodox approach elicited a characteristically Brunellian response: 'Such a course may possibly be unusual in the execution of Government work, but it involves only an amount of responsibility which men in my profession are accustomed to take. It is only by the prompt and independent actions of a single individual entrusted with such powers that expedition can be secured and vexatious and mischievous delays avoided. These buildings, if wanted at all, must be wanted before they can possibly arrive.’

A site was chosen at Renkioi, and one of Brunel’s assistants, William Brunton, was dispatched to prepare the ground and superintend erection. By late March the first consignments of 23 shiploads were ready. Duplicate plans were sent by different ships, and Brunel supplied detailed instructions and a team of skilled men for the various tasks. His understanding of the need for good hygiene and his attention to detail is reflected in providing printed instructions for the proper use of a mechanical water closet – many of the men would never have seen one before.

The death rate at Renkioi was tiny compared with Scutari. Brunel wrote to Brunton: ‘Everybody here expresses themselves highly satisfied with everybody there and what we have done. I should wish to show that it was no spirit but just a sober exercise of common sense.'.

By Anthony Lambert

MRT lecturer

Image: Plan of a ward building, Renkioi Hospital, designed by Brunel. Credit: Creative Commons Licence CC BY 4.0

View tours led by Anthony Lambert